Graphite Animal Drawings

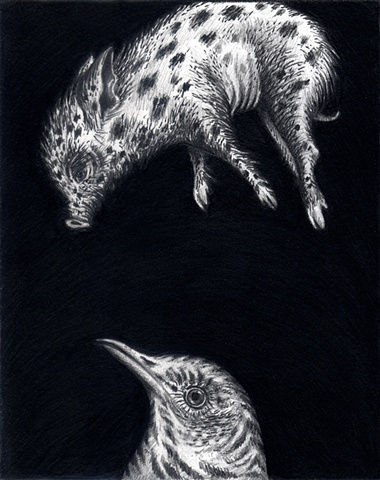

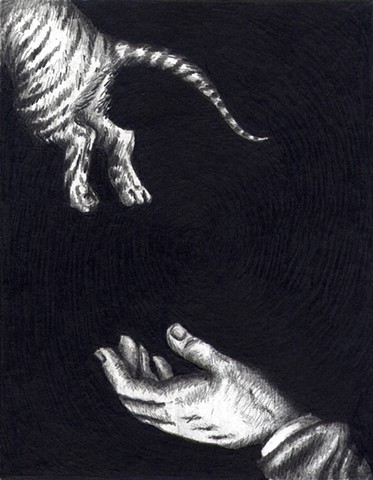

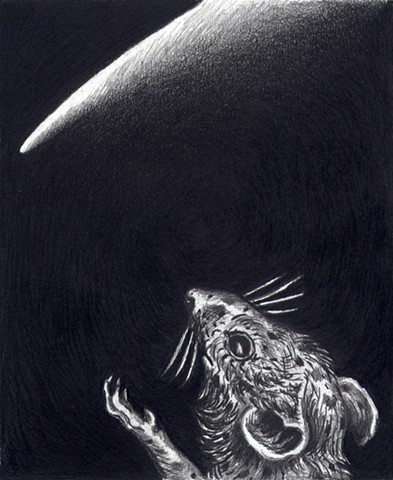

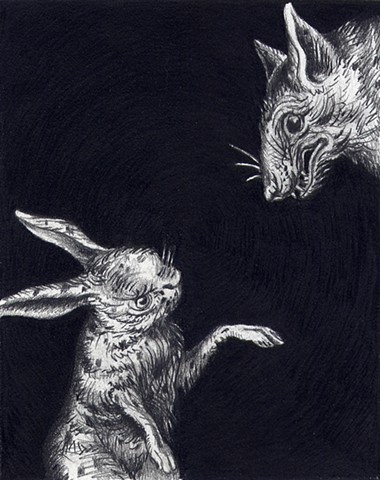

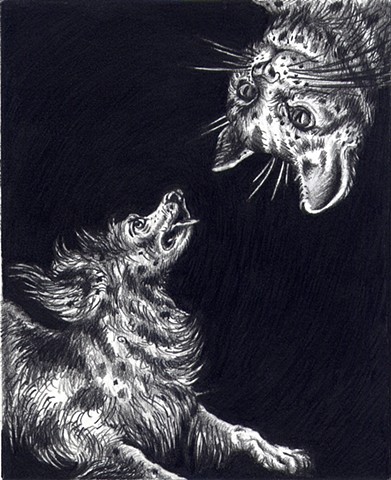

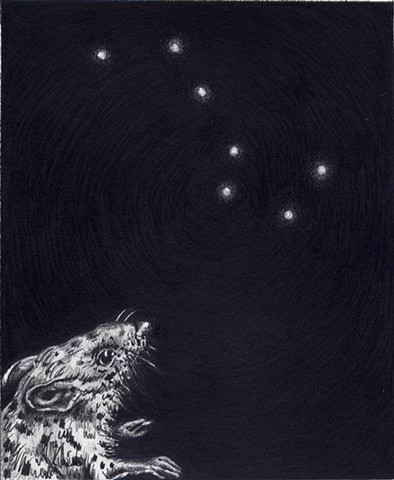

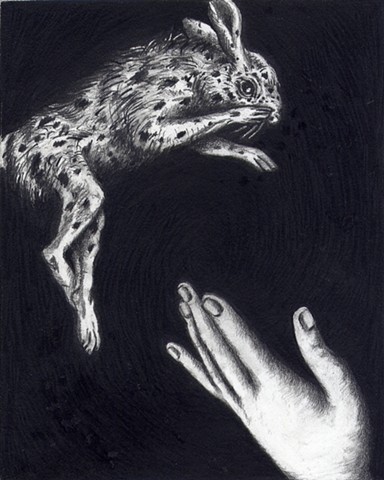

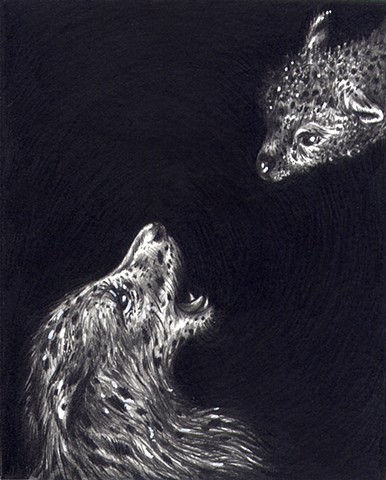

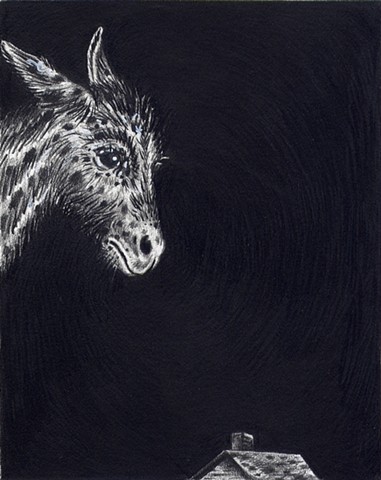

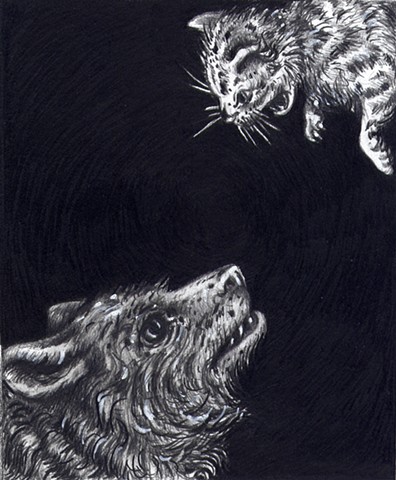

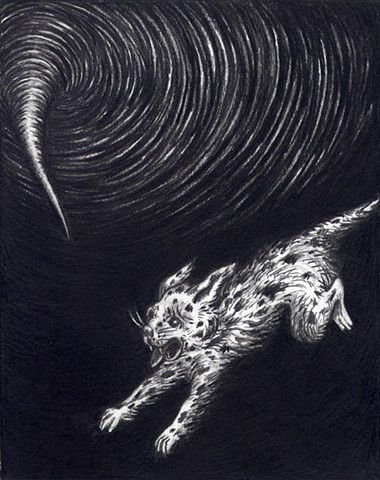

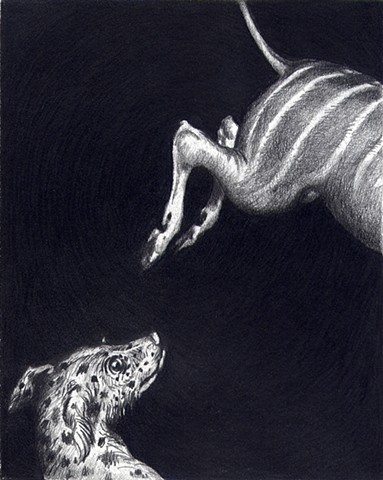

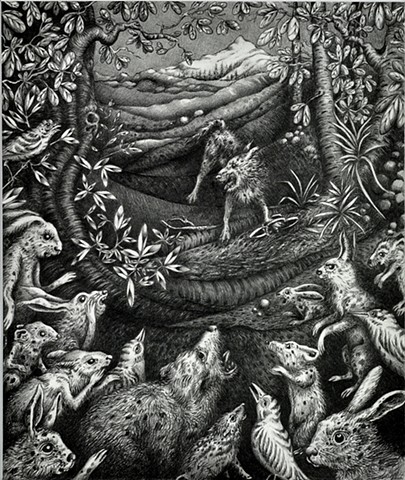

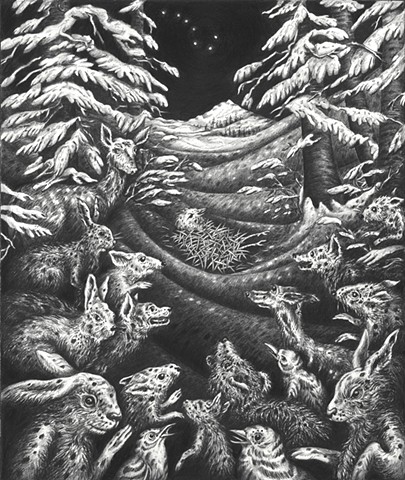

"Encounters" is a new series of small graphite drawings depicting animals.

Like many people who live in Idaho, I am an animal advocate and an obsessive hiker who encounters various animals in the wild in addition to the domestic animals that enrich my daily life. Rabbits, foxes, coyotes, wolves, badgers, deer, skunks, snakes, songbirds, birds of prey, moose, elk, and bears join me in nature, and I am made aware of the presence of more elusive creatures such as bobcats and cougars through the tracks they leave as evidence.

In 1978 the zoologist Donald R. Griffin proposed his philosophy of “cognitive ethology” (animal thinking).1 This theory is now usually referred to as “animal consciousness, or the idea that animals are sentient creatures. Many people have witnessed this phenomenon when interacting with their pets (for example, a dog that becomes “depressed” during the absence of his/her owner). I believe wild animals display a similar range of feelings.

Animals have appeared in my drawings since the early 1980’s (in 1981 two of my drawings depicting birds and wolf-like dogs were included in an exhibition titled Sawtooths and Other Ranges of Imagination at the National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution).

Like many children I grew up reading fairy tales such as Brer Rabbit, Reynard the Fox and Aesop’s Fables. A few years ago I began looking at 19th century illustrators of these books and other animal stories. Three famous artists, J.J. Grandville, Charles H. Bennett and Wilhelm von Kaulbach anthropomorphize animals by dressing them as humans to act in nature as a commentary on human vices or foibles.2

In most of my recent drawings (and unlike Grandville, Bennett and Kaulbach) I place the animals—without clothing—in an abstract space that allows for a broad range of situations and emotions. Animals are depicted in curious encounters with other animals, objects, or entities. This interaction occurs within a limited amount of dense, black ether-like space that facilitates the cropping of their bodies and odd relationships of scale and placement. The creatures act surprisingly, or perhaps uncomfortably with their counterparts. Particular arrangements create a mini-narrative or implied dialogue that ranges from playful to confrontational. By emphasizing the heads of most of these creatures I draw attention to their eyes and ears as emblems of their sensitivity. The animals are depicted as aware of each other or aware of their viewers as they perform in the roles I assign to them. Animals are signifiers of beauty and power—essences I strive for in all of my work.

1. His theory is further explained in: Donald R. Griffin, Animal Minds: Beyond Cognition to Consciousness (University of Chicago Press, 2001).

2. J.J. Grandville, Scenes de la vie privee et publique des animaux (1842); Charles .H. Bennett, The Fables of Aesop and Others, Translated into Human Nature (W. Kent & Co., 1857); and Wilhelm von Kaulbach, illustrator, Reynard the Fox (1860).

click on small image to view each drawing in the series